Having recently defined myself as a “spaceaholic” – I love designing big gardens - I have found myself suddenly faced with a clamour for all things small – designing small gardens, writing about small gardens and speaking about them.

Although we might think about small gardens as a local phenomenon in our own city or town, they are in fact a global issue for all urban dwellers. Our gardens are getting smaller year by year as population density in major cities and conurbations increases. For some city dwellers their only outdoor space is now a balcony and with the average UK garden now only 90m² across the whole nation, it’s easy to see how some gardens must be really tiny.

The difficulty is that many small garden owners simply won’t accept that their gardens are – well – small. As designers we are regularly assailed by a list of client requirements including children’s play, outdoor dining, productive planting, water features, storage or outdoor kitchens for a space no bigger than an average living room. An outdoor dining space for a family of four would be approximately 4m x 4m and sometimes that might be the extent of the space available. All small garden owners need to admit to the space limitations of their plots – the sooner the better so that we can get on with some sound design advice.

A host of issues come with spatially challenged plots. High density living compromises privacy, with neighbours close and sometimes looking in from above. The more we try to enclose our gardens or create arbors or pergolas to screen from prying eyes, the more we contribute to the sense of enclosure and to shade. Most boundary and screening structures cast shadows into the garden, sometimes restricting use and always restricting planting options. We need to plant for prevailing conditions, choosing shade tolerant species rather than roses or colourful perennials that need the sun – we can always go elsewhere to visit bigger plant collections. Use plants in small spaces to work hard for you rather than seeing the garden as a plant collection.

Planting will soften and screen boundaries but it needs to be big and bold; no shrinking violets in small gardens. This will help to disguise physical boundaries and create a more characterful space. Think about plants with height too as they will link the garden with the sky. Darker colours for the boundaries will also minimise their impact allowing colour in flower or sculpture and ornament to be the eye catching focal point.

The more the client wish list can be simplified and reduced the more space becomes available for the real priorities – more generous furniture, outdoor fireplaces, sculpture or planting borders.

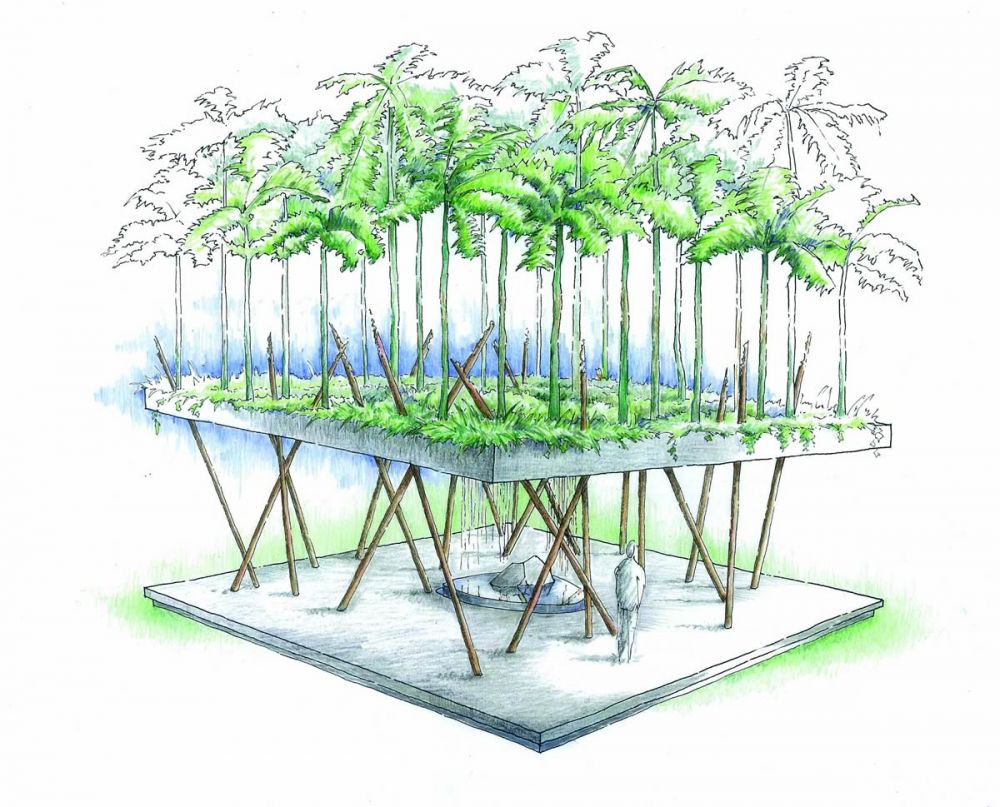

Linking in to the global picture I recently visited Singapore and Seattle – the former to prepare for the Singapore Garden Festival later in the year (16-24 Aug 2014); the latter to speak at a symposium on small gardens. Common themes were evident such as the increase in urban density, larger new developments at the expense of garden space and the use of planting on buildings to create a more sustainable balance in the urban infrastructure. Gardens and planting hold the key to healthier cities – the individual spaces may be small but together these green oases create a critical planting mass that the city desperately needs for clean air, sustainable drainage and psychological well being.

For Singapore the incredible humidity means that gardens are often viewed from temperature controlled interiors whereas in London we try to open up our interiors to the garden space. Both approaches need strong planting in order to deliver a punch and a sense of therapeutic nature.

In Seattle, the concept of shared space as opposed to separate garden plots suggested a different approach to the small garden. Dan and Ann Streissguth have gardened a substantial plot in Seattle for most of their married life before handing over 95% of the plot to the city authorities and to the wider community. Anyone can come and go, relax in the garden or even help with the gardening. The move prevented threatened development of the site in future and has become a local community treasure. Perhaps a future of garden sharing will allow a more flexible use of our small gardens in which we retain sufficient space for our private use but handover the rest in a shared venture for more productive and flexible green spaces. The great garden squares of London did exactly that two centuries ago and are now considered one of London’s greatest assets. What goes around comes around perhaps; what do we have to lose?